Jackson Hole News and Guide: Snake River Fund Director Jared Baecker

Longtime Safari Guide Turns to Advocacy

Snake River Fund Director Jared Baecker looks back at the path to his stewardship job.

In his earliest days interpreting Jackson Hole’s flora, fauna and natural order for tourists, Jared Baecker wasn’t exactly fighting for exclusive viewings.

As the lead guide for Teton Science Schools’ Wildlife Expeditions starting in 2002, the young naturalist was on the ground floor of the valley’s now-well-developed wildlife safari industry. Wolves and grizzly bears were just returning to Jackson Hole after being extirpated during the previous century, and there were comparatively few private wildlife watchers around vying for a view, let alone commercial tour operators.

“There was no competition,” Baecker said. “TSS just purchased the business from Tom Segerstrom, and we were the only one. There was no Jackson Hole Wildlife Safaris, no Eco Tours, no Spring Creek, nobody was doing it. It was just this really incredible time out in the field when you would just explore Grand Teton.

“It was awesome,” he said. “It was pretty humbling for somebody who grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, to have all this wildness at your fingertips.”

Even when the office is a wild landscape, a job is a job, and after 14 years Baecker was looking to shake it up. The growth of summer tourism and the wildlife-watching industry was part of the decision, but he was also just ready to move on.

A position had opened at the Snake River Fund that blended being outdoors on the water with education. An advocacy organization, the fund had been around since the turn of the century, and Baecker’s first gig with the nonprofit as program director was well established and not fundamentally different from his past professional experience. It was almost a seamless transition from working mostly with tourists to mostly with kids, Baecker said.

The larger transition came a couple of years later, when Len Carlman moved on from his executive director role. Baecker stepped in to take the helm. In quick order he was wading into weighty issues about watershed protection and working closely with a board of directors for the first time.

“It was a huge shift of responsibility into the management and advocate role,” Baecker said “It’s definitely opened my eyes to public policy and process and rules and regulations on so many levels, whether it’s local county level … all the way up to federal roles associated with Wild and Scenic river designations.”

Baecker was following in the footsteps of the likes of Aaron Pruzan, Paul Bruun and Frank Ewing, who helped form the Snake River Fund in the late 1990s in response to a Bridger-Teton National Forest discussion about starting a system for charging fees for access. The organization went on to play a major role in community debate about the development of the Canyon Club (now Snake River Sporting Club), successfully lobbied for a Wild and Scenic Rivers Act designation for the Snake River headwaters and has been in the thick of numerous other watershed debates.

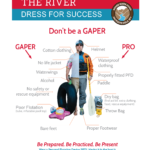

Today one of the big issues Baecker is grappling with is skyrocketing use of the Snake River and the increasing need for crowd control and education. The river has grown into a major economic engine for the community, he said, and it’s being used now more than ever.

“That’s true just in the 17, 18 years I’ve lived here,” Baecker said. “It used to be you would see a raft or a drift boat and a handful of cars at the boat ramp, and you’d know exactly who that was who was guiding that fishing trip.

“Today every pickup truck in the town of Jackson is towing a raft or a drift boat behind it during the summer. That’s a wonderful thing because it shows that people love the resource, but managing it and treating it with respect and focusing on leave-no-trace ethics is something that we have to embrace as a community.”

Baecker’s attraction to wild, Western landscapes stemmed largely from his upbringing. Although raised in a decidedly urban East Coast city, he spent parts of his summers at western Massachusetts’ Camp Becket, and family vacations took him to places like New Hampshire’s White Mountains and Vermont’s Green Mountains to ski and hike.

By the time Baecker was graduating from high school in 1995, a through-hike of the Appalachian Trail, not college, was his immediate dream. In his late-teens gap year he completed the 2,190-mile walk in the woods in five months and 12 days and had an epiphany along the way.

“I realized the East Coast was a great place to grow up,” Baecker said, “but it was not where my future was potentially going to be.”

He passed the next five years in Missoula, studying wildlife biology at the University of Montana. From there he bounced around research jobs. He studied Hawaii’s endemic honeycreepers, spent six months in Alaska’s Denali National Park looking at how climate change was influencing populations of small mammals, and sojourned in Jerome, Idaho, for a mule deer monitoring project. His first Jackson Hole job was at the Wildlife Conservation Society, studying wolverines in the Teton Range under Rachel Wigglesworth.

The 14-year stint at Teton Science Schools kept Baecker grounded in Jackson Hole, as did landing an affordable house in Wilson through the Teton County Housing Authority in 2009.

Summer is the season for celebrating for Baecker, who spends as much time outdoors as he can.

“I love exploring big aspen groves with my puppy,” he said. “That’s how I can spend my days: looking for great gray owls with my dog and spending as much time on the water with friends and family as I can.”

While he’s at it Baecker is often trying to impart an appreciation for the Snake River’s headwaters.

“I would love for our community to look at the waters we have as a cherished public resource, instead of just something we drive over on the bridge,” Baecker said. “Often it’s easy to look away from the rivers, and I would love for people to look towards them.”